TOKYO – I landed in Tokyo last week – for the first time since the great earthquake and tsunami hit Japan 75 days ago.

While the reason for my visit was to see my aging mother, I arrived with much trepidation— largely driven by what I didn’t know. I had no real feel for the magnitude of impact the recent disaster must have had on the country and its people. Everything I learned about what happened on March 11th — and what I deduced about it — seemed almost theoretical.

Walking through the customs at Narita airport initially calmed me. People, places and things were as efficient, clean and as orderly as always. Nothing at Narita was broken; the whole scene screamed out the Japanese national motto: “Business as usual.”

The rude awakening, however, hit when I attempted to buy a train ticket at the airport. Narita Express trains are running on an irregular schedule, “due to the Great Tohoku Kanto earthquake,” according to a woman at the Japan Railway ticket counter. The next available Narita Express train I could take wasn’t due for three hours. While surprised, I told myself, “Oh, well. So, I’ll take the bus to Yokohama.”

Arriving at Yokohama station after 90 minutes on the bus, I discovered that Japan Railway had stopped running every escalator to every platform at every station. I could either hike up a stairway that looked like it went to the stars, or I could line up at one lonesome elevator — which I did, not because I’m not fit, but because I was schlepping a suitcase. I looked wistfully at a nearby escalator, chained and motionless, bearing a notice that read: “Please cooperate with us in conserving energy.”

In the public rest room at the station, the toilets — thank God — were flushing. Everything seemed normal until I went to dry my hands. Every dryer had a notice, saying: “Please cooperate with us in conserving energy.”

I walked out waving my hands, and resigned to the message of post-tsunami Japan. Forget the little conveniences we’ve all come to take for granted. It’s post-war all over again — and saving energy was everybody’s job, just like it had been in 1946.

Finally installed on a local train, I opened a newspaper. While the Asahi Shimbun had a number of stories related to the quake’s aftermath, the most eye-catching was a large map of Tohoku and Kanto.

It mapped out each village and town affected by the disaster, complete with death tolls, the missing and those evacuated to temporary facilities in each municipality. The newspaper also devotes a sizable space for a list of full names of “Those who passed away.” This has become a regular feature of each newspaper, day in and day out. Clearly, Japanese authorities are still discovering bodies. When those bodies are identified and publicly acknowledged, the newspaper adds a measure of finality.

But the thing that really freaked me out was the daily nuclear report (it looks a lot like a weather forecast map) – listing radiation levels in the air in various cities in Tohoku and Kanto. Again, this is now a regular feature -- both on NHK (Japan’s public broadcast) news, and in the paper.

I learned that Chigasaki, where my mother lives, registered 0.052 microsieverts per hour the day before my plane landed. Although this was a marked difference from the 6.6 microsieverts found in Namie-cho, a town 31 kilometers northwest of the stricken Fukushima Daiichi power plant, I wasn’t quite sure what to make of either number.

I was supposed to feel reassured about the low-level of radiation in the city I was heading for. But then, I also know that there’s no scientific data, at this point, on the impact on human bodies of a low-level dosage of radiation over a long period of time. It’s the unknown that fuels everyone’s fear.

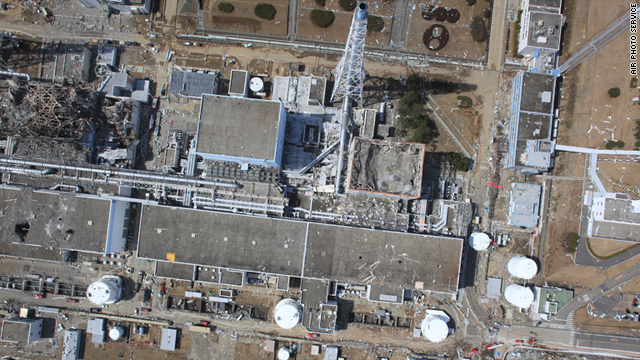

The Tokyo Electric Power Co. (Tepco) six-reactor complex on Japan’s northeastern coast continues emitting radiation into the air and water. Tepco itself has said it will not be able to bring the three heavily damaged reactors under control until late this year or early next year. That’s the hard reality.

No solutions in sight for containment

While the plant continues to spew radioactivity, Japan’s largest electric power company will be pumping water into the damaged reactors and venting radioactive steam for a year or more. Tepco has built a low-level waste storage facility on the site. But it has no plans to move the waste elsewhere.

More bad news came from Tepco last Thursday [May 27th]. A new leak in a storage container had dumped an additional 60 tons of radioactive water into the environment.

It’s clear that no credible solutions are in sight to contain the deteriorating reactors. No concrete plans are laid out for how to deal with the growing nuclear waste, either.

Look no further than a recent controversy over the radiation exposure limit for schoolchildren in Japan. The government set off an uproar in April when it set a radiation exposure limit of 20 millisieverts per year, the same dosage the International Commission on Radiation Protection recommends for nuclear plant workers.

Under pressure, the Japanese government announced last week that it will pay schools near the Fukushima nuclear plant to remove radioactive topsoil; it re-set the target radiation exposure for schoolchildren at one-twentieth the previous limit.

NHK had reported that before this new policy was announced, one school in Fukushima had jumped the gun and scraped the surface of the radioactive soil on its playground. The school’s quick action and independent thinking seemed laudable. But there was a hitch. They had no place to put the contaminated soil. No farmers could use it and no neighbors wanted it in their backyard. The school was told to keep the heap of radioactive soil in the middle of the schoolyard — for now.

The Japanese may be better prepared for earthquakes than any other country. But this is scant consolation in today’s post-earthquake and tsunami problem — the absence of a plan by the combined leadership of government and industry for the future, especially when it comes to dealing with nuclear energy.

It’s only been a week, but I’m starved for information. This is the big worry.

Or, more accurately put, I worry about the tendency for “self-restraint” among Japanese bureaucrats, government officials, politicians, industry leaders and even some in the academia here to keep disclosure of information at a minimum. Early in the crisis, for instance, the Japanese government had detailed information on radiation levels in towns near the Fukushima nuclear plant. Government officials only released the data via the Internet. The names of town were masked – reportedly to prevent mass flights of panicked people, causing “unnecessary” chaos or confusion in the society.

Similarly, in my humble opinion, Japanese consumers are as guilty as their so-called leaders.

Harmful rumors

“Fuhyo higai” is Japanese term I had never heard until I got here this time. Roughly translated as “harmful rumors,” it discourages anyone from discussing the safety of produce or products originating in affected areas. People who live in the “Fuhyo Higai” belt will be compensated by Tepco and the Japanese government. But it’s almost as though the government would prefer that people don’t know they’re victims until they get their compensation. I understand the need to keep “harmful rumors” from running rampant. But the Japanese consumers and the Japanese press are turning common sense into a moratorium on tough questions. It’s almost eerie.

I can live with fewer pachinko parlors and vending machines on the streets in Japan – both of which were labeled power hogs by the governor of Tokyo. I am OK with fewer neon signs in the Ginza; I am certainly for Japanese companies closing their offices at 4:30 p.m. so that they can turn off lights, sending employees home early and allowing them to work from home. Flex-time might even catch on in Japan.

The Japanese auto and auto-parts manufacturers decided to close on Thursdays and Fridays, operating instead on Saturdays and Sundays from July to September to limit power use during the midweek peak.

Because of the damage to power plants in the eastern part of the country, the government has set a target to cut electricity use by manufacturers by 15% this summer, when demand normally picks up with air-conditioner usage. Certain industries deemed critical to the Japanese economy – such as Japan’s semiconductor sector – are exempt from the regulation. But the nation is united behind the 15 percent conservation target. Most experts I talked to remain confident that Japan can stay in business without any serious power interruptions through the summer.

The Japanese are great at setting, communicating and achieving goals like that 15-percent cut. In contrast, we tend not to discuss, or make plans, or even face up to issues — like the nuclear mess in Fukushima — that require solutions more complicated than the March of Dimes. So, as we worry mutely about Fuhyo-Higai, deplore speculation, and tut-tut worst-case scenarios, little is said in public.

The silence is deafening.

It extends to the big uncertainty about the next big quake. What’s the worst that could happen?

Everyone knows the answer: Tokyo. Masaya Ishida, publisher of EE Times Japan, along with 13 million other people, lives here. He said, “The problem is that we don’t know when the next big one will hit us. It can be three years from now, or 300 years.”

Quiet, Ishida-san! If we don’t talk about it, maybe it will go away.

We 'came close' to losing northern Japan

We 'came close' to losing northern Japan  TEPCO admits to more possible meltdowns

TEPCO admits to more possible meltdowns  Orphaned by the tsunami

Orphaned by the tsunami  MORE than three quarters of French people believe the country should follow Germany and withdraw from nuclear energy, a new survey has found.

MORE than three quarters of French people believe the country should follow Germany and withdraw from nuclear energy, a new survey has found.